What to do in the meantime?

Disclaimer: This is a repurposed passage from my previous article -Immigration, Privatization, and Ownership in The Statist Commonwealth

Over the next week or so, I plan to repackage some of my main points presented in that article in more digestible chunks, I will also expand on some points if I find necessary. Immigration is currently a hot topic in libertarian circles, and doing this will allow me to more easily cite arguments I’ve made without asking people to read a very long article and it will give me a chance to expand on some points as my thinking has evolved.

Hope you enjoy.

𝑾𝒉𝒂𝒕 𝒕𝒐 𝒅𝒐 𝒊𝒏 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒎𝒆𝒂𝒏𝒕𝒊𝒎𝒆?

Engrossed in the libertarian enigma of immigration is the question of who has the legitimate ownership of the “public spaces”. (I’ve offered my answer above, but I want to bring forth another argument I have yet to address before we close.)

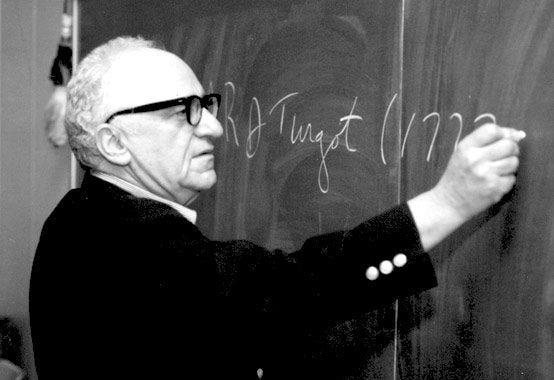

The father of modern libertarianism, Murray N. Rothbard wrote a challenging critique in chapter 40 of “Making Economic Sense” titled: “WHAT TO DO UNTIL PRIVATIZATION COMES”

Rothbard asserts that until we reach a private property society, all public property should be treated as if it were private in order to establish certain norms on the property that are not possible if the property is open to everyone.

Rothbard writes:

But what should be done in the meantime?

There are two possible theories. One, which is now predominant in our courts and among left-liberalism, and has been adopted by some libertarians, is that so long as any activity is public, the squalor must be maximized. For some murky reason, a public operation must be run as a slum and not in any way like a business, minimizing service to consumers on behalf of the unsupported “right” of “equal access” of everyone to those facilities. Among liberals and socialists, laissez- faire capitalism is routinely denounced as the “law of the jungle.” But this ”equal-access” view deliberately brings the rule of the jungle into every area of government activity, thereby destroying the very purpose of the activity itself. For example: the government, owner of the public schools, does not have the regular right of any private school owner to kick out incorrigible students, to keep order in the class, or to teach what parents want to be taught.

The government, in contrast to any private street or neighborhood owner, has no right to prevent bums from living on and soiling the street and harassing and threatening innocent citizens; instead, the bums have the right to free “speech” and a much broader term, free “expression,” which they of course would not have in a truly private street, mall, or shopping center. Similarly, in a recent case in New Jersey, the court ruled that public libraries did not have the right to expel bums who were living in the library, were clearly not using the library for scholarly purposes, and were driving innocent citizens away by their stench and their lewd behavior.

And finally, the City University of New York, once a fine institution with high academic standards, has been reduced to a hollow shell by the policy of “open admissions,” by which, in effect, every moron living in New York City is entitled to a college education. That the ACLU and left-liberalism eagerly promote this policy is understandable: their objective is to make the entire society the sort of squalid jungle they have already insured in the public sector, as well as in any area of the private sector they can find to be touched with a public purpose. But why do some libertarians support these “rights” with equal fervor? There seem to be only two ways to explain the embrace of this ideology by libertarians. Either they embrace the jungle with the same fervor as left-liberals, which makes them simply another variant of leftist; or they believe in the old maxim of the worse the better, to try to deliberately make government activities as horrible as possible so as to shock people into rapid privatization. If the latter is the reason, I can only say that the strategy is both deeply immoral and not likely to achieve success.

It is deeply immoral for obvious reasons, and no arcane ethical theory is required to see it; the American public has been suffering from statism long enough, without libertarians heaping more logs onto the flames. And it is probably destined to fail, because such consequences are too vague and remote to count upon, and further because the public, as they catch on, will realize that the libertarians all along and in practice have been part of the problem and not part of the solution.

Hence, libertarians who might be sound in the remote reaches of high theory, are so devoid of common sense and out of touch with the concerns of real people (who, for example, walk the streets, use the public libraries, and send their kids to public schools) that they unfortunately wind up discrediting both themselves (which is no great loss) and libertarian theory itself. What then is the second, and far preferable, theory of how to run government operations, within the goals for cutting the budget and ultimate privatization?

Simply, to run it for the designed purpose (as a school, a thoroughfare, a library, etc.) as efficiently and in as businesslike a manner as possible. These operations will never do as well as when they are finally privatized; but in the meantime, that vast majority of us who live in the real world will have our lives made more tolerable and satisfying.

Murray Rothbard is without a doubt one of my most foundational ideological influences, and I owe a great deal of gratitude to his work. With that being said, we should never allow our heroes to be beyond reproach, to do so would be a disservice to them, for they would surely respect honest critique as opposed to affirmation born out of cowardice.

While I certainly agree with Rothbard that the state’s control of these resources generates negative externalities for many, I do not think Rothbard’s argument here holds the weight he wishes. The assertion that it should be run like it was under the control of a private owner doesn’t tell us anything. There is no platonic ideal of what a private owner should do on the grounds of their property, and even if there was, it certainly could not be deduced from the libertarian axiom that Rothbard vigorously supported throughout his life. What one private owner would want to do on their property may be completely contrary to what another may wish to do on their respective property. The libertarian merely asserts that one has an exclusive claim to their property, they do not assert that there is a correct way for them to use their property vis-à-vis libertarianism.

To illustrate this, a person who runs his property communally where anyone is free to use his property is as much of a private owner dictating terms on his property as the property owner who restricts all but a certain few on a number of conditions is, as long as he acquired the property legitimately.

A private church and a private brothel are both equally private property in the eyes of the libertarian.

I would agree with Rothbard that the state doesn’t own the property in question, but this does not entail that the state has the right to use the property as if it was their private business, not because everyone has a right to it, but rather because this would be a rights violation of the legitimate owner’s claim, which can’t be justified on libertarian grounds.

The argument that Rothbard proposes above may be persuasive if viewed from a consequentialist or utilitarian lens, but the very libertarian foundation that Rothbard spent his life developing was not based on consequentialist or utilitarian considerations. I can only view Rothbard’s turn here as somewhat disappointingly inconsistent with his previous work, which stands as an indispensable cornucopia in the libertarian canon. If you agree with Rothbard’s argument here, that is understandable, but I don’t think you can claim this is Rothbard deriving something from his theory, and instead, should be viewed as a standalone proposition.

End of the original section

———————————————

Added context from the future:

Rereading this, I think it’s important to point out some possibilities on the nature of the “public property” in question. For any given piece of public property, it is either legitimately owned by someone despite the state disregarding the private owner’s ownership claim, or, it is unowned.

If it is legitimately privately owned, then only the owner may justly set the terms (if any) upon use of the property. For the state to not aggress in this instance, the state would have to honor the private owner’s wishes and not place any added restrictions upon the use of the land. While this is possible, it is highly unlikely. Many modern proponents of Rothbard’s above position wish to treat the land in question as a private property owner would, but they have no way of knowing how this owner would treat the land without asking them. I’ll concede that it may be difficult to track down the dispossessed owner to ask them what rules they wish to have on their now stolen property, but it’s not per se impossible. So they resort to assumptions about what they think an owner would or wouldn’t allow, which would ultimately be an arbitrary policy, but it’s not per se aggression. In defense of this position, we could analogize this to an unconscious person who needs medical attention, they are not conscious to grant consent to transport them to a hospital and perform invasive but life-saving procedures, so we are taking a gamble that they would consent to this procedure if they could.

Now that I’ve defended this position to the extent that I think it can be principally defended, I’d like to critique why this analogy is not perfect:

In the analogy, the unconscious person cannot be asked - in the case of the dispossessed owner, it is possible in most cases to track down the legitimate owner and ask them what they wish to be done with the property. In cases where the legitimate owner has died, this may be trickier, but if they have any offspring we can defer to them as to what rules they wish to have on this property.

Furthermore, If the unconscious patient were to wake up, they could determine the act of transporting them to the hospital and invasive procedures to be an act of aggression, just as the dispossessed owner could determine any state simulacrum of private property norms over their property to be an act of aggression.

If the “public property” in question has no ascertainable legitimate owner, then the state, nor anyone else, has the right to place restrictions on unowned resources, as this would constitute an act of “forestalling”, an act of exclusion placed on a piece of land/resources prior to them being homesteaded, which is an act of aggression by libertarian standards.

I appreciate any constructive criticism in the comments. Thanks for reading.

I agree that there is "no Platonic ideal" that would cover how the entire sphere of the private sector would operate, but I also think Murray Rothbard nevertheless provided the best framework to consider.

I fully agree with him in that too many libertarians seem to lose sight on practical questions because they are too hung up in the theoretical world.

We've also got the "is-ought" issue at hand. The descriptive can't pin down the prescriptive.

But we can build on the church-brothel example. They're obviously run on different and specified incentive structures. What are each looking for? What are their target markets? Who if anyone would they exclude?

The same goes for assessing a factory and a retail store. One would be more "closed borders" than the other.

Assessments can be made, they just can't be universalized for every subset of commercial life.