Among libertarians, immigration is one of the most hotly debated topics. We see a divide of viewpoints between those who view the immigrant as a non-aggressive traveler, versus those who view the immigrant as an invader on land that is not rightfully theirs to tread. In this article, I’m going to be going over arguments proposed by distinguished libertarian scholars, and other common arguments against free immigration that I feel miss the mark. I’ve often debated this topic on social media off and on, and I feel I can not properly do justice to the argument in short form. One of my goals for this article is to cover as much of this topic as extensively as I can from a libertarian rights perspective and reduce the arguments against free immigration down to their fundamental essence (and hopefully show why they’re wrong.)

We’ll start with the strongest argument against free immigration.

Distinguished libertarian theorist, Dr. Hans-Hermann Hoppe presents an argument on libertarian grounds which has become colloquially become known as “The Net Taxpayer Argument” this argument would seemingly justify state immigration restrictions deduced from libertarian property norms, but does it hold up to scrutiny? It will be my prerogative in this article to suggest and to layout arguments as to why it does not hold up to further inquiry and to put forward my deduction from Austro-libertarian axioms on the question of immigration. This is a controversial topic for many, but I do ask that all who continue forward view my criticism in a purely academic sense with the best faith possible. Dr. Hoppe is one of the most distinguished theorists in the libertarian pantheon and is no doubt a brilliant man with many indispensable contributions that libertarians have to be thankful for. I do not undertake this endeavor lightly, or without forethought.

𝑾𝒉𝒂𝒕 𝒊𝒔 𝑻𝒉𝒆 𝑵𝒆𝒕 𝑻𝒂𝒙𝒑𝒂𝒚𝒆𝒓 𝑨𝒓𝒈𝒖𝒎𝒆𝒏𝒕?

In ‘A Realistic Libertarianism’ 1 Dr. Hoppe makes the claim that the public property of the state is not to be treated as unowned property, as many libertarians prior to Hoppe’s argument had originally taken for granted, but rather, it is to be treated as owned by the net taxpayers residing in the country itself, as their property (taxes) has been unjustly funneled into the creation and maintenance of this public property, and for this reason, no one would have a right to enter or use the public property (roads, schools, public lands, etc) contrary to the taxpayers’ wishes. So in the interim to an anarchist society, the state has a duty to act as a trustee and protect the property of the taxpayers from encroachment by non-taxpayers. This assumption is held by many libertarians today and seems to have a strong intuitive sway. After all, why would someone who has money invested in a public resource, whether stolen or not, not have more of a property claim to that resource compared to someone who has not paid anything into it?

Hoppe states:

The second possible way out is to claim that all so-called public property – the property controlled by local, regional or central government – is akin to open frontier, with free and unrestricted access. Yet this is certainly erroneous. From the fact that government property is illegitimate because it is based on prior expropriations, it does not follow that it is un-owned and free-for-all. It has been funded through local, regional, national or federal tax payments, and it is the payers of these taxes, then, and no one else, who are the legitimate owners of all public property. They cannot exercise their right – that right has been arrogated by the State – but they are the legitimate owners.

In my view, there exists a fundamental error in Dr. Hoppe’s analysis. One that has caused many libertarians to advocate fundamentally unlibertarian policy proposals. I would like to do my best at showing why Dr. Hoppe is wrong in this regard through a deductive argument of mine from an axiomatic libertarian starting point and through a series of reductio ad absurdums, and ultimately what I think is the correct position on immigration from a libertarian perspective.

𝑾𝒉𝒚 𝑻𝒉𝒆 𝑵𝒆𝒕 𝑻𝒂𝒙𝒑𝒂𝒚𝒆𝒓 𝑨𝒓𝒈𝒖𝒎𝒆𝒏𝒕 𝒊𝒔 𝑾𝒓𝒐𝒏𝒈

I believe the fatal flaw in professor Hoppe’s claim stems from a misapplication of title transfer theory concerning property (specifically, stolen property), and as such, I claim he deduces an incorrect conclusion from false premises. Under libertarian property theory, the first user (or the first user of an abandoned resource) to incorporate a resource into their ongoing projects acquires a right of ownership over the resource, (a right is a justified claim or action that is permissible for the right bearer to enforce, which would entail an obligation on all other parties to abstain from interfering in said right) and thus they have the absolute right to exclude others from it, and by extension, limit access to it based on their arbitrary parameters. Because the owner is the only agent with a rightful claim, the owner is the only one who has a right to legitimately transfer the title to another. As the owners of a given resource are the only ones who can authorize a title transfer. This implies the title must be legitimately owned by the current possessors engaged in trade. We must keep this fundamental starting point and argument in mind as we go forward, as everything I’m about to present will be deduced from it.

Because the owner is the only agent who has the authorization to transfer the title, it then follows that any sale of the title by a usurper is automatically fraudulent, and if the sale is fraudulent, no title is actually transferred. Let us examine this in an allegory to elucidate the underlying principle more tangibly.

Alice, a wealthy businesswoman, is robbed of $30,000 by Bob. Bob, who is now the unjust possessor of the money, buys a used car from Carl. Now Bob is in possession of the car, and Carl is in possession of the $30,000. Because Bob purchased the car with Alice’s stolen money, does Alice own the car?

No, absolutely not.

Bob had no right to use or transfer Alice’s $30,000 in exchange for the car, and Carl only exchanged the car on the condition that he would be the title owner of the $30,000, and because Carl did not become the legitimate owner, the condition of the exchange was not fulfilled, which makes the transaction fraudulent. So it follows that Alice would be owed the $30,000 and Carl would still own the car, as no title was transferred in reality, the “transaction” was all a sleight of hand.

When the state expropriates taxpayer money to build a park or any public infrastructure, the money is not legitimately owned by the state, and thus, the state has no right to transfer it to another party as compensation to the laborers to build the park in question. So when the state uses taxes to “purchase” materials and labor from some 3rd party, the 3rd party is being defrauded as they only exchanged with the state on the condition that they would legitimately own the title to the tax money, and as we demonstrated above, this would mean that any economic arrangement the state makes is fraudulent, and thus the respective property titles never actually transfer from their legitimate owners. This has profound implications, as the laborers, and material suppliers would be the owners of ALL public infrastructure in the U.S. and not the taxpayers.

This deduction comes from the simple premise that only the legitimate owner has a right to authorize action with or on their property; something all libertarians should hold as axiomatic.

Indulge me a moment and allow me to state this more formally:

[X = Justified owner / Y = resource justly owned by X / Z = usurper of Y / A = Another legitimate title holder]

[ 1.] The first agent to incorporate a resource into their ongoing uses becomes the legitimate owner of the resource (X). [premise]

[ 2.] The legitimate owner (X) retains the exclusive right and title to control the resource (Y) and as a result, retains the right to set terms and conditions on the use and disposal of the resource. [premise]

[ 3.] If one has the exclusive right to authorize use over a particular resource, then a latecomer must acquire consensual authorization from the legitimate titleholder in order to justly act upon the resource. [1, 2]

[ 4.] A latecomer who uses the legitimately owned resources of another without the consensual authorization of the legitimate owner is a usurper of title (Z). [2, 3]

[ 5.] Z cannot justly use Y without the consensual authorization of X. [3, 4]

[ 6.] X has the only justified claim to authorize the use of Y. [1, 2, 3]

[ 7.] If title can be legitimately acquired, then it can be legitimately abandoned or transferred. [1, 2]

[ 8.] Only a person with a justified claim to a resource may consensually authorize a transfer of the title of the resource to another (A). [1, 2, 3, 7]

[ 9.] Title can be legitimately transferred by its justified claimants iff both parties mutually consent, and all subsequent conditions made by the parties are met. [2, 3, 7, 8]

[ 10.] If one or both parties are delinquent in the terms of conditional transfer, then the conditions are not met. [2, 3, 8, 9]

[ 11.] If the conditions of the title transfer are not met, then no title is transferred between the parties. [2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 9, 10]

[ 12.] Any attempt to engage in the use of a legitimate owner’s resource without justly acquiring the title whether through force or deception is usurpation. [1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10]

[ 13.] Only X may legitimately transfer Y to A. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

[ 14.] Z has no right to transfer the title of Y to A. [1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

[ 15.] If Z does not have the consensual authorization to transfer Y to A, then A has no right to be in possession of Y. [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 12]

[ 16.] If A’s conditions were not met, then no title has justly been transferred. [2, 8, 9, 10, 11]

[17.] Since Z had no consensual authorization to trade Y to A, then A will not justly own Y. [14, 15]

[18.] Since A only offered up his legitimately owned title to Z in exchange for the title of Y, A’s conditions were not met. [5, 8, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]

[ 19.] Therefore, no title has been transferred. The title of the usurped resources remains with the original owners prior to the usurpation, thus X’s and A’s property titles were never transferred for one another. [1-18]

I believe my argument presented above is logically valid and sound from a libertarian axiomatic starting point, and therefore would show that Hoppe’s formulation of the net taxpayers being the owners of a country's public property is incorrect. I expect and would love for anyone who disagrees with my argument to engage with it and show where in the chain I made an error of logic.

It would be negligent of me to continue on to other arguments and criticisms before I present potential objections of my own argument and answer them, so let us begin.

𝑶𝑩𝑱𝑬𝑪𝑻𝑰𝑶𝑵𝑺:

Objection 1. Who is to say that the legitimate owner does not consent to have his resources used to purchase the title to another resource? After all, isn’t the state merely acting as a steward of the legitimate owner’s property?

Response: This would certainly be true if the state was acting as a mere intermediary between buyer and seller, but this is not the case due to the state never acquiring legitimate authorization from the property owner to act as an agent in the first place. The state never acquired legitimate authorization since they are in possession of taxpayers’ resources through a means of coercion, and we cannot declare something is consensual while under the threat of coercion. If you think it isn’t coercive once the state already has your money, try demanding it back and see what happens.

Objection 2. The taxpayers would want their taxes used in one way or another, why does this not count as consent?

Response: People may want to actualize certain ends while they are under coercion, but we cannot say they are consensually authorizing them. As an example, a person who has fallen victim to a mugger with a gun may want to hand over his wallet to the mugger given the alternative, or a person may vote for one presidential candidate over another due to a cost-benefit analysis, but no libertarian would regard this as a free choice devoid of coercion, which is a prerequisite for consensual authorization.

Objection 3. If It is my money, why am I not owed restitution in the form of the state’s property? That doesn’t sound libertarian at all!

Response: Because the state does not own the property, the state is a predator, not a producer. It has nothing it hasn’t stolen from you or someone else in its possession. As I showed above, the state did not legitimately acquire title from you or the material/labor supplier in the creation of any public property, and thus by libertarian norms, the public spaces would be owned by the material/labor supplier, whereas you would be entitled to the money itself as restitution.

Objection 4. Most property titles in the US cannot justly be tracked to the first owner in an unbroken chain of consensual transfers, thus wouldn’t this make all property titles dubious? And thus would this not mean that the current occupants could not use or authorize the use of the property by following the logic of your argument?

Response: This is absolutely true, but unless one can show they have a higher claim to the property by showing it was stolen and determining who had the rightful claim to it, then the current possessors have the best claim to the property by default. Much like a person is presumed to be innocent until proven guilty even if they have committed a crime. With the state, we can show that their possession of the taxpayer property is coercive and thus illegitimate.

𝑯𝒐𝒑𝒑𝒆 𝒐𝒏 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒅𝒊𝒇𝒇𝒆𝒓𝒆𝒏𝒄𝒆 𝒃𝒆𝒕𝒘𝒆𝒆𝒏 𝑭𝒓𝒆𝒆 𝑻𝒓𝒂𝒅𝒆 𝒂𝒏𝒅 𝑰𝒎𝒎𝒊𝒈𝒓𝒂𝒕𝒊𝒐𝒏

In “The Cases for Free Trade and Restricted Immigration,” 2 Dr. Hoppe brings forth a distinction between “free trade” and “immigration.” In Hoppe’s view, The act of free trade can be justified due to the goods being voluntarily traded and accepted by both parties, as opposed to an immigrant who partakes in migration to a new country without the consent of any of the property owners in the country. This creates, in Hoppe’s view, a fundamental distinction in which the immigrant is to be viewed as an invader, as opposed to goods that can only be traded with the consensual authorization of the parties. Hoppe writes:

The phenomena of trade and immigration are different in a fundamental respect, and the meaning of “free” and “restricted” in conjunction with both terms is categorically different. People can move and migrate; goods and services, of themselves, cannot.

Put differently, while someone can migrate from one place to another without anyone else wanting him to do so, goods and services cannot be shipped from place to place unless both sender and receiver agree. Trivial as this distinction may appear, it has momentous consequences. For free in conjunction with trade then means trade by invitation of private households and firms only; and restricted trade does not mean protection of households and firms from uninvited goods or services, but invasion and abrogation of the right of private households and firms to extend or deny invitations to their own property. In contrast, free in conjunction with immigration does not mean immigration by invitation of individual households and firms, but unwanted invasion or forced integration; and restricted immigration actually means, or at least can mean, the protection of private households and firms from unwanted invasion and forced integration. Hence, in advocating free trade and restricted immigration, one follows the same principle: requiring an invitation for people as for goods and services.

However, with respect to the movement of people, the same government will have to do more in order to fulfill its protective function than merely permit events to take their own course, because people, unlike products, possess a will and can migrate. Accordingly, population movements, unlike product shipments, are not per se mutually beneficial events because they are not always — necessarily and invariably — the result of an agreement between a specific receiver and sender.

Under Dr. Hoppe’s framework here, it would seem that the immigrant can be restricted from the public property as it is, in reality, the private property of the taxpayers. The problem here is that once we assume this is the case, then Hoppe’s provided justification for free trade in the current context becomes dubious. Hoppe claims that free trade is justified where immigration is not because the transaction is consensual between the parties - but wait a moment - if we must treat the roads and interstates as private property, then the taxpayers of the country would have to consensually authorize the transportation of the goods in question being transported for the trade to be truly consensual by all parties involved, and if they do not, (and they currently do not) then it seems the transportation of goods itself without permission in public areas would count as trespass. It doesn’t seem at all apparent why the taxpayers would feel the need to restrict only immigrants on public property. The taxpayers would have just as much of a right to stop the transportation of any goods they desired from traveling on their road to get from A to B, in the same way, you or I would have the right to restrict a person from entering our property if they were in possession of a gun, drugs, alcohol, or even if they were thought to be potentially carrying a virus or any other innumerable variables we could conceive.

Let us engage in a thought experiment:

Alice, who lives in New York City, wishes to visit Bob in Florida for his Birthday and bring him a gift, a 3D printer. Alice travels down I-95 and runs into a complication, a mandatory checkpoint! It turns out the majority of the taxpayers have a left-wing bent and have banned the possession of guns or any equipment that could be used to make a firearm, on their property. At this point, Alice is left with no choice but to turn around and go home or have her 3D printer seized. The result is that Alice is trapped if she wishes to leave her home with a gun, or any equipment that could produce a firearm due to the collective dictates of the taxpayers.

This wouldn’t be limited to interstates or local roads, but all public spaces and utilities monopolized by the state. Given that the vast majority of taxpayers in this country have a cultural propensity for restrictions on anything from guns, to pornography, to alcohol, to public prayer, to even people with an incorrect vaccine status, it would be no leap of the imagination to conceive that these restrictions would manifest in this scenario.

Under this framework, a citizen traveling with any restricted goods is as much of an aggressor as the immigrant who walks over the border or uses a public road. This type of scenario could happen in any configuration, but I’m sure you see the absurdity here. Unlike an anarchist society, the state would be making these decisions in the interim as a steward of the taxpayer’s property, and as a result, they would still have an unjust monopoly on the roads, leaving one with no alternative when it comes to travel. For this reason, I don’t think Dr. Hoppe’s distinction between free trade and immigration holds as much weight as he suggests.

Another problem I have yet to discuss is one I feel many proponents of Dr. Hoppe’s argument fail to consider. Let’s again assume, for the sake of argument, that Hoppe is correct that the net taxpayers are indeed the legitimate owners of the public property in the US. This would still not justify the exclusion of immigrants from crossing most of the border territory as I will show.

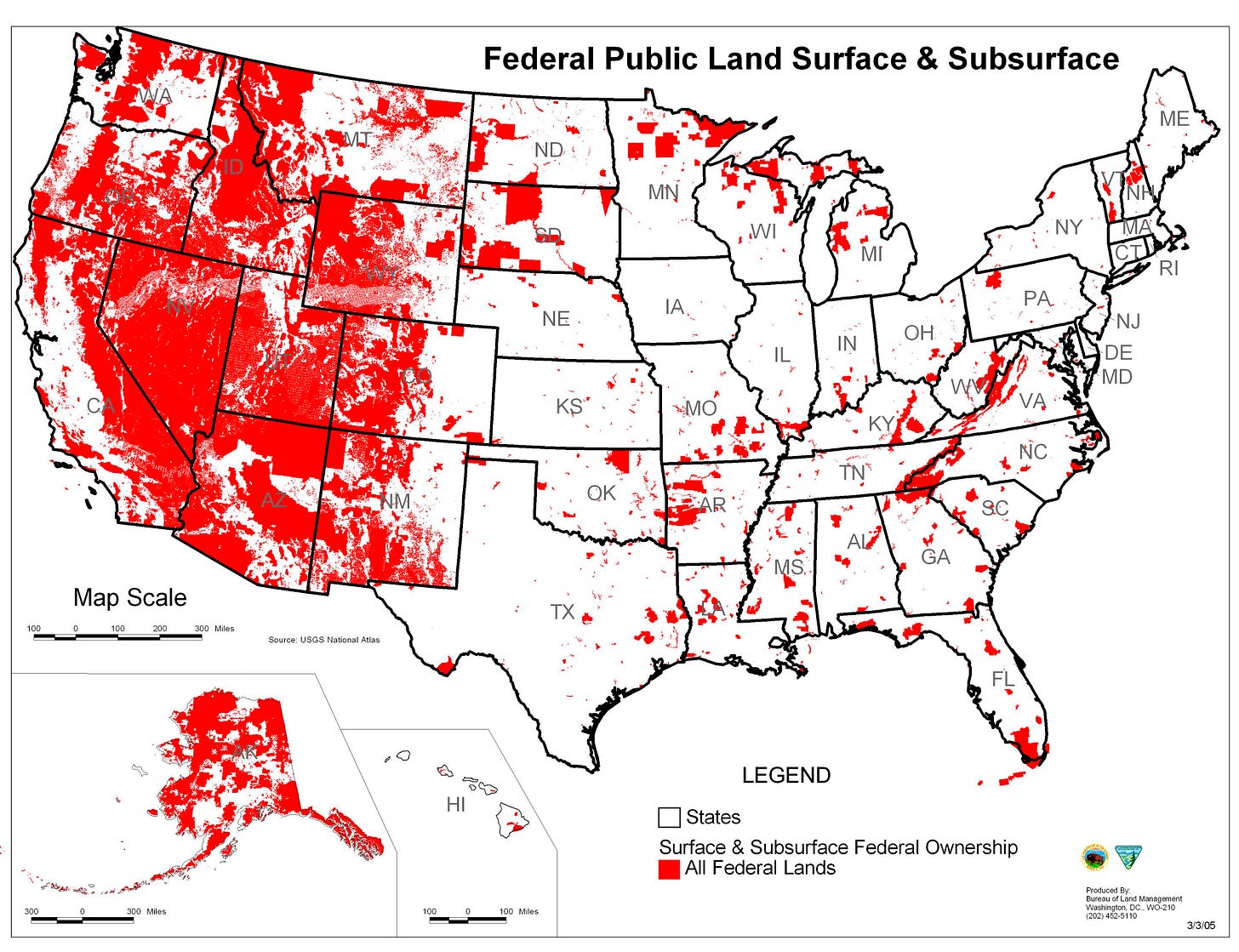

For me to demonstrate why this is the case, we must return to fundamentals. The justification for Agent A to use force on Agent B to exclude them from territory C is contingent upon Agent A first homesteading territory C in question, thereby rendering Agent B’s use of Territory C without permission to be invasive, and thereby rendering Agent A’s recourse to force to be defensive. Homesteading requires a conscious systematic use of the unowned territory in question. One does not have the right to exclude anyone from entering any landmass unless the entrance would constitute an initiation of force into one’s boundaries, which would require by necessity, that the territory would first have to be homesteaded by a prior user. Much of the land in the U.S. west of The Mississippi River is being held captive by the US government, including much of the border territories, and it has not been homesteaded by anyone, let alone the government. The government violently excluding people from using the land cannot count as homesteading, as homesteading is a prerequisite for the right of exclusion in the first place.

As much of the land has never been homesteaded, this would necessarily imply that no title has been generated in regards to this land, (unless the state physically removed the prior users) and as a result, if no title exists for this land, then the taxpayers could never have purchased legitimate ownership to a non-existent title.

This would render most state border patrol on the southern border to be aggressive even if we assume the net taxpayers own homesteaded public property.

Dr. Hoppe continues in “The Cases for Free Trade and Restricted Immigration” by envisioning what an Anarcho-Capitalist society will look like and its implications for immigration.

Hoppe states:

The guiding principle of a high-wage-area country’s immigration policy follows from the insight that immigration, to be free in the same sense as trade is free, must be invited immigration. The details follow from the further elucidation and exemplification of the concept of invitation vs. invasion and forced integration.

For this purpose, it is necessary to assume first, as a conceptual benchmark, the existence of what political philosophers have described as a private property anarchy, anarcho-capitalism, or ordered anarchy: all land is privately owned, including all streets, rivers, airports, harbors, etc. With respect to some pieces of land, the property title may be unrestricted, that is, the owner is permitted to do with his property whatever he pleases as long as he does not physically damage the property of others. With respect to other territories, the property title may be more or less restricted. As is currently the case in some developments, the owner may be bound by contractual limitations on what he can do with his property (restrictive covenants, voluntary zoning), which might include residential rather than commercial use, no buildings more than four stories high, no sale or rent to unmarried couples, smokers, or Germans, for instance.

Clearly, in this kind of society, there is no such thing as freedom of immigration, or an immigrant’s right of way. What does exist is the freedom of independent private property owners to admit or exclude others from their own property in accordance with their own restricted or unrestricted property titles. Admission to some territories might be easy, while to others it might be nearly impossible. Moreover, admission to one party’s property does not imply the “freedom to move around,” unless other property owners have agreed to such movements. There will be as much immigration or non-immigration, inclusivity or exclusivity, desegregation or segregation, non-discrimination or discrimination as individual owners or owners associations desire.

I’m going to engage in what will be seen as some libertarian heterodoxy here. I do not believe my deviation will be the result of an unprincipled intuition, but on the contrary, it will be a fulfillment of principle consistent with the libertarian framework.

I will argue that all people possess a de facto (but not a de jure) right to movement. I will engage in a reductio ad absurdum through the use of another allegory to elucidate my position:

Alice is taking a walk in the woods, deep through the forest where no owned property exists for miles. While walking, Alice encounters a group of 14 men who encircle her and stand shoulder to shoulder. The men demand that she pay them $250 and they will let her pass. As the men each have an ownership claim to their body, is Alice obligated by libertarian property theory to pay the fee to pass, or may she nudge her way out of the encirclement?

It would seem on its face absurd to assume that Alice could be justly forestalled by the men until she pays, but how can we reconcile this with libertarian theory? After all, wouldn’t Alice attempting to nudge her way through be a violation of the men’s property rights to their bodies?

Well, no, not really. Under standard libertarian doctrine, one is permitted to do anything they wish with their property so long as they do not engage in aggression with it.

I fail to draw a principled distinction between what the men did to Alice, and imprisoning someone against their will with a cage. It is only a difference in degree, as opposed to a difference in kind. So if we, as libertarian anarchists, can use our principles to oppose unjust imprisonment, then I think we are obligated to say the men are using their bodies to aggress, and thus Alice has a right to move through them with the least amount of force required.

If we extrapolate this to external property, what I’ve described is commonly known as an “Easement of Necessity” in The Common Law tradition. An easement of necessity would recognize the impermissibility of property owners to use their property to blockade another property owner, and thus would grant the trapped owner a right to pass on another’s property with the least amount of force possible, and only through a designated area and only for travel, not for cultivation or any other extended purposes.

I would also express my disagreement with Dr. Hoppe’s (and most libertarian’s) assertion that an Anarcho-capitalist society must exist absent of anything we could conceive of as “public property”. While it is true that “public property” is often correlated with state expropriation, it doesn’t have to be, nor has it always been historically.

Roderick T. Long, an Austro-libertarian philosopher, explains this position well in his article “In Defense of Public Space” 3

Long writes:

On the libertarian view, we have a right to the fruit of our labor, and we also have a right to what people freely give us. Public property can arise in both these ways.

Consider a village near a lake. It is common for the villagers to walk down to the lake to go fishing. In the early days of the community it's hard to get to the lake because of all the bushes and fallen branches in the way. But over time, the way is cleared and a path forms — not through any centrally coordinated effort, but simply as a result of all the individuals walking that way day after day.

The cleared path is the product of labor — not any individual's labor, but all of them together. If one villager decided to take advantage of the now-created path by setting up a gate and charging tolls, he would be violating the collective property right that the villagers together have earned.

Public property can also be the product of gift. In 19th-century England, it was common for roads to be built privately and then donated to the public for free use. This was done not out of altruism but because the roadbuilders owned land and businesses alongside the site of the new road, and they knew that having a road there would increase the value of their land and attract more customers to their businesses. Thus, the unorganized public can legitimately come to own land, both through original acquisition (the mixing of labor) and through voluntary transfer.

Under this framework provided by Long, we see it is perfectly consistent with libertarian property ownership for both localized “public” property that was created through the decentralized emergence of collective action, and the transfer of title to multiple parties. Taking Long’s example even further, it would not be impermissible for a property owner in an Anarcho-capitalist society to transfer the title of their property to every person on earth, thus recreating something that would approximate the features of public property without the state’s expropriation.

𝑨𝒏 𝑨𝒑𝒑𝒆𝒂𝒍 𝒕𝒐 𝑾𝒆𝒍𝒇𝒂𝒓𝒆

I’m going to address other common arguments against free immigration to take a closer examination of proposed immigration restrictions by people in the liberty movement that they believe are consistent with the foundations of libertarianism. Specifically, we'll look at restrictions on immigration concerning welfare on the basis of libertarian ethics.

The argument is generally presented as follows:

While the absence of state borders may be the end goal, we cannot allow immigrants to enter the country while we are continuously burdened by a welfare state. The welfare state will socialize a percentage of the costs of these immigrants onto the taxpayer, and thus, it would be defensive to use force on the migrant to stop them from entering the country to protect the taxpayers.

Like the net taxpayer argument, this position seems to have a dominant amount of intuitive sway with many libertarians. A large number of libertarians view the act of restricting immigration as a defensive use of force to protect the taxpayers from further aggression, but is the case in reality, and is it justified on libertarian grounds?

I believe that this argument, and others that share its form all fall victim to reductio ad absurdums concerning libertarian beliefs. Allow me to demonstrate just a few:

Imagine a scenario where the United States Government began to use taxpayer dollars to incentivize reproduction due to falling birth rates. Out of concern for this, a more right-wing government wanting to promote family values begins to create an escrow of tax money that is automatically sent to married couples on the condition that they are having a child. The payout is a total of $100,000 per child paid out in an annual portion every year until they are 18 years of age, as children are a huge commitment that many families cannot financially support given the cost of living. This incentivizes more childbirth, families would have more children, thus demanding more taxation to cover the cost of this program.

Now let us suppose we have two groups, A and B. Group A are low-income households and pay little to no income tax, while Group B are high-income households and pay a large portion of the total income taxes collected by the government in the country. Group A is incentivized to have children, many of them. In doing so, group A will now be collecting much more tax income than they have ever paid in, especially if they have more than one child (which they would be incentivized in having), and in doing so, they are now net tax consumers. The Government’s plan has worked! birthrates are growing at an exponential rate, dramatically so for group A. Group B, is very displeased with this arrangement for obvious reasons, as they are in effect, subsidizing other people’s children who pay practically nothing back tax-wise.

The question for libertarians is this: Would group B (or the state acting in B’s interest) have a right to forcibly prevent group A from producing children?

If one supports the premise that the state is justified in using force on the immigrant to prevent them from entering the country for the possibility the state will subsidize them upon entry, then I contend that the libertarian is logically bound to say that group B, or the state representing group B, would indeed have the right to forcibly restrict reproduction by group A.

After all, a child being born into the world and the immigrant share certain overlapping features that pertain to this line of reasoning. Both the immigrant and the newborn are people who previously did not exist within the country they now find themselves in until they did. The newborn and the immigrant both represent a new addition to the social system they were once not a part of and paid nothing into. Both are susceptible to being net tax consumers as opposed to net taxpayers. The distinctions that do exist between them should not be relevant to the libertarian arguing for immigration restrictions, as these differences amount to superfluous attributes that don’t factor into the contents of their argument.

I think the conclusion reached from the premise above is absurd, and not valid on libertarian grounds for the same reason I think the conclusions of immigration restrictions using this argument are absurd based on the same premise.

I believe I have made my point clearly, but I would like to be as rigorous and unyielding as I possibly can through the use of another reductio ad absurdum before we move forward.

Let’s imagine we live in a society where the entire healthcare industry is socialized. Every person is forced by law to pay into this system, and there are no private healthcare alternatives legally available. In this society, every person is forced to subsidize the healthcare of those who are unhealthy, old, and those who are born with preexisting conditions that require constant medical intervention on a regular basis. Through this presumption, we can deduce that a healthier person will put less stress on the taxpayers as compared to those who live a very unhealthy lifestyle, whether that be through poor dietary habits, lack of exercise, drug or alcohol abuse, or all of the above, etc.

Given this assumption, the unhealthy are likely to be akin to net tax-consumers, as opposed to net taxpayers due to the frequency and severity of their healthcare needs. This creates an asymmetry where the resources of those who are healthy are being forcibly redistributed and consumed by those who are unhealthy.

The more this asymmetry continues, the more resources will be demanded from those who are healthy, thus putting more upward monetary pressure on the healthy.

So now we once again pose the question to libertarians:

Until we can remove this socialization, would healthy people in this society have a right to forcibly stop people from engaging in unhealthy behavior? Would a healthy person have the right to forcibly stop a person from consuming alcohol, drugs, or fast food? Would it be justified to force fast-food establishments to serve only healthy food, and if they did not, force them out of business? Would it be justified to force people to exercise?

I think we can all see the absurdity here, but if one bases their argument on the premise of having the right to use force on people who would inadvertently put more pressure on the taxpayers, then I think they would once again be logically obligated to say yes to all of the above.

Perhaps you’ve read my uses of reductio ad absurdum and you remain unconvinced. Perhaps you do think that the conclusions I presented would be justified under libertarian norms; I will attempt to show why this is incorrect.

Under the normative libertarian theory, each person has a right not to be aggressed against. A right is a justified claim or action that entails an obligation on every other person to not interfere with the enactment of one’s right (think of obligations as the natural flipside or dovetail of rights). All rights are relational to something or someone. The libertarian believes that each person has a right to be free from the initiation of force, fraud, and coercion.

A having a right to X implies that B must not interfere with A’s right to X, and if B interferes, A can justly use force to defend his right from B’s encroachment. Now to tie it all in, let’s assume that C coerces A and tells him that he will rob him every day until A assaults his neighbor, B. Does A have a right to assault B to defend himself from C? No.

Remember, B also has a right to be free from aggression. In this scenario, B being free from aggression is disconnectedly hurting A, as if A assaulted B, A would be free from C’s coercion, but B is not the efficient cause of A’s predicament. C is the efficient cause, and C coercing A does not invalidate B’s right to be free from aggression. So even under duress, A does not have a right to assault B even if it would save him from C’s coercion.

To tie it back, this should show that the existence of a state coercing the populace does not give the populace a right to direct their force at people who are not aggressing. Even if this would lessen the burden the populace faces.

I hope this clarified why advocating for state immigration restrictions on the basis of welfare cannot coherently conform to a libertarian theory of rights and obligations.

𝑻𝒉𝒆 𝑫𝒆𝒎𝒐𝒄𝒓𝒂𝒄𝒚 𝑨𝒓𝒈𝒖𝒎𝒆𝒏𝒕

Similar to the welfare argument that we discussed above, The democracy argument is often employed to justify the permissibility of immigration restrictions on the basis of the political beliefs of the migrants who cross the border. Much like many of the other arguments for immigration restriction, this argument comes across as common sense to most, and I can understand and sympathize with people’s concerns, even if I do not advocate for their policies out of principle.

The argument as it is generally presented:

Immigrants statistically vote for an increase in government programs, resulting in aggression, which compounds the problem of democracy that libertarians already suffer with. This exacerbation renders the cause of liberty’s progress more arduous and it becomes much harder to reduce the size of the state. For this reason, it is justified to stop the immigrant from entering the country to avoid this catastrophic problem.

I will concede that the problem of being locked into a polity where our fate is decided by the masses of people who believe they have a right to select a ruler for their neighbor is a terrible position to find oneself in, but I do not think this argument alone justifies restrictions against immigration itself on a libertarian basis, it would only justify a restriction on voting where the vote would grow the state as opposed to shrinking it.

We have to distinguish between something critical in our analysis of this argument. I believe anyone presenting this argument is engaged in a causal fallacy, as the act of crossing the border and entering a country is not the same action as the immigrant voting for more government programs, even if they are likely to do so afterward. The immigrant being in the country is a necessary attribute the immigrant must possess to be able to vote, but that necessity alone is not the sufficient cause for their vote.

So the libertarian who uses this argument has two options:

A) The libertarian concludes that voting can be aggression.

B) The libertarian concludes that voting cannot be aggression.

If the libertarian chooses A, (which would seem the prudent choice if they wish to reach the desired conclusion of their argument) then this would still fail to justify restricting the immigrant from crossing the state’s border on the basis of democracy, as the border crossing would not be the aggression in itself. Choice A would only justify stopping the immigrant from voting.

If the libertarian chooses B, they have no basis on normative libertarian grounds for stopping the immigrant from voting, and by extension, entering the country on the basis of stopping them from using the democratic process.

This argument (much like the argument that preceded it) opens itself up to a devastating reductio ad absurdum if one wishes to argue for it from a libertarian foundation. Often, this argument is employed by libertarians who believe that Democrats are often worse for liberty on average than Republicans. The veracity of this claim is debatable when one factors in longer time horizons in American History, and the vagueness of what constitutes a “Republican” or “Democrat” at any given time outside of an ostensible title, but for the purposes of this argument, I will accept the claim as true. The next assertion is that immigrants tend to vote for democrat politicians and policies when they do vote. (I will also accept this as true)

Suppose that a libertarian suggests that using force on an immigrant is justified to stop them from entering the country to stop them from voting for Democratic politicians. Once we concede the justification of stopping the immigrant from entering the country with force on the grounds that they will be a net increase in the democrat’s voting bloc, then why would it not be justified under this logic to stop children from entering this country through natural birth who will grow up in democratic households to registered democrat parents? After all, under this argument, every new child that is born to democrat parents is likely going to be a net increase of the democrat’s voting bloc in 18 years. The difference in this scenario between the child born to democrat parents who will grow up and likely vote democrat and the immigrant who is likely to vote democrat is a difference in the timeframe, thus it is a difference of degree and not a difference of kind.

Many may object to my reductio ad absurdum; they may see my analogy as vulgar, and they may accuse me of indulging in too much liberty to make the connection between the child and the immigrant. While there are many unique attributes differentiating the immigrant and the child, those differences are ultimately extraneous in relation to the argument presented. An analogy can still be apt, even when the properties being compared have impertinent elements that are not at all analogous. Analogies need not be equivalencies.

Another reductio ad absurdum one could employ is this:

If it is permissible to use force to stop immigrants from coming into the united states because they may vote for politicians that will increase the size of the state, then what principled reason stops us from applying this principle domestically? After all, a democrat migrating from California to Texas is just as much of a net increase in the local democratic voting bloc in Texas as the immigrant from Mexico would be to the United States nationally. If it would be justified to forcefully stop people from migrating from California to Texas, then why stop there? What about restricting with force people from Roma Texas from entering Perryton Texas until we can end the tyranny of democracy? The end result of this would be a travel lockdown within the united states where no one of X political persuasion could enter the jurisdiction of Y or X/Y jurisdictions for the same reason the libertarian wishes to restrict immigration. This would mean even domestically, people could not travel from region to region to trade goods or offer up their labor to others outside of the political jurisdiction they were born into. There is no non-arbitrary line we can draw here to mitigate this conclusion.

If a libertarian tries to escape this conclusion by asserting that the immigrant is a foreigner as a distinct reason why the conclusion does not follow, then they are engaging in the informal fallacy known as Special Pleading. It is Special Pleading because the libertarian is drawing an arbitrary, unprincipled exception to the argument they have themselves proposed. The distinction is arbitrary being that, under Libertarian norms, a person’s rights and obligations are natural to their humanity, and thus a person in Romania, Pakistan, Brazil, Mexico, The United States, etc, all have the same moral rights and obligations irrespective of geography, nationality, race, etc.

Let’s tackle an obvious objection one might have to the reductio ad absurdum:

Libertarian anarchists tend to support secession and decentralization in general, so why would it be wrong to bar people from politically invading these regions? After all, in a democracy, the more people in a particular polity, the less sovereignty you have as a political agent and the less worth your vote will carry. So it seems perfectly rational from a decentralized perspective that we would wish to decouple ourselves from potential outside influences that would attempt to enter and subvert our decentralized aims.

I sympathize and endorse the libertarian’s commitment to decentralization and radical secession, but I feel this objection kicks the can and doesn’t address the obvious problem. Secession and decentralization alone do not imply that it would be impermissible for one to cross into the country of another. There is nothing inherently contradictory about favoring decentralization and secession from a political polity and a person being justified to exist within the geography of the polity by extension even if they are not a part of it, (in fact, that is the goal).

So this criticism is ultimately a deflection (with a well-meaning endpoint) away from the main point proposed by the argument.

The answer to this dilemma from a libertarian perspective should be clear: If voting is aggression, then it would be justified to restrict people from accessing the political process. Where libertarians get this wrong is by assuming they would be justified in using force against a person in response to a non-violent activity because they feel that the agent in engaging in the prior non-violent activity will raise the probability they will aggress in the future. The libertarian must never fall prey to the allure of using violence to deter pre-crime.

We must always distinguish between where the aggression starts, and where it ends before we advocate for sweeping policy proposals based on generalizations that would limit our ability to articulate the line clearly.

𝑻𝒉𝒆 𝑪𝒓𝒊𝒎𝒆 𝑨𝒓𝒈𝒖𝒎𝒆𝒏𝒕

This argument is generally employed by conservatives and other elements of the right, but a few libertarians tend to use this as a fallback reason as to why immigration should be restricted. So, like the arguments above, I’d like to present it and offer a rebuttal:

An increase in immigration correlates with an increase in net crime. These immigrants come from cultures that do not share our values or respect property rights, and by letting them come here, we are allowing these people the chance to commit injustices against our citizens that would not have occurred had these people never been allowed in.

If you had a jar of Jellybeans, and 1 out of 100 were poisoned, would you still take a chance at consuming them? How many times would you take that chance? If you wouldn’t gamble with the jelly beans, why would you gamble with hordes of immigrants who may be hostile to you, your family, and your way of life?

Therefore in order to protect our life, liberty, and property, we must end the Russian roulette of immigration.

This line of reasoning has many fatal flaws not just for libertarians, but for practically any political persuasion. Paranoia permeates this proposition, and in doing so, lays the groundwork for the destruction of all rights if one were to apply it consistently.

Imagine that you’re invited over to a house party, and you’re the first person to arrive. Being the first person at the party means the probability of you being aggressed against by other guests is currently 0. Now let’s assume more people start to show up over time. Every new attendee at the party raises the probability that you will incur violence from 0 to > 0. Does this fact permit the first guest to forcefully stop the upcoming attendees from entering due to this increased risk? You would be hard-pressed to find anyone who would say yes, even if they supported immigration restrictions founded upon the same principle.

To exhibit the absurdity even further, why not apply this reasoning in terms of gun ownership? Every time someone acquires a gun they previously did not possess, this also increases the probability from 0 to > 0 that they will use this gun to murder someone. Should it then be permissible to restrict others from owning weapons due to the increase in risk factors? Most conservatives and every libertarian (hopefully) would say no.

Going back to the most applicable reductio ad absurdum in terms of arguments for immigration restrictions, why would this not apply to children?

If it is justified to restrict immigration using the reasoning that some could engage in violent activity once they arrive, then this would also apply to children. As presented in the argument, if 1 out of 100 Jellybeans were poisoned, then would we accept the risk of eating any of them? Consider how many children grow up and commit crimes. If it is impermissible to allow immigrants into the country for the mere potential a minority of them will commit crimes, why is it ok for children to enter the country through birth when a minority of them could just as well grow up to commit crimes? After all, every murderer and rapist would never have been able to inflict their indignities on the innocent had they never been born in the first place. If it would be impermissible to allow immigrants to enter because they could become violent once they are here, then it would seemingly be impermissible to allow children to be born as they could be just as violent when they grow up based on this same reasoning.

Perhaps one could counter my argument here and advocate for restricted immigration where the immigrants are vetted before allowing them into society as opposed to a fully closed border. While this would escape the vulgar conclusion of my reductio ad absurdum, it would open them up to a revised, and nevertheless obscene conclusion. Would anyone think it would be morally justified to restrict couples from reproducing until they could prove to the state that they would not raise a child in an environment that could be conducive to a life of criminality, such as poverty? Surely this would be an absurd notion to the vast majority.

There is no reason why this principle would be limited to national borders as opposed to state, city, and county borders, etc. After all, every new migrant from one state to another adds to the probability that you or someone in your state will experience violence from this new visitor. So why would it not be justified to close the border of states within the U.S., or even cities within states, or blocks within cities based on the reasoning that immigration restrictions are justified due to the potential of crime from additional incomers?

(Many of these arguments share similar weaknesses, so it can seem like I am merely going in circles by repeating myself, but I believe it is important to show why these propositions are inadequate in the most thorough ways possible. I appreciate your indulgence if you have made it this far.)

The Crime Argument appeals to our inner sense of fear of the unknown “other”, and by extension, our desire for ourselves and our loved ones to remain as safe as possible, but it ultimately resorts to a grotesque application of injustice. The presumption of innocence is an indispensable component of justice, not merely for libertarianism, but for any political theory that wishes to act in accordance with that which is right. If we abandon the presumption of innocence as the starting point, then we must dispense with any notion of justice or rights altogether. If the state or any social order has the right to detain us until we can prove we are not dangerous, then they can lock us up indefinitely until we can pass their arbitrary standard, and if you look around the last couple of years, you’ll find that is exactly what has happened.

Rejecting the presumption of innocence entails the desecration of the philosophical and legal standard of onus probandi (The Burden of Proof). For example, If Bob claims that Alice stole his wallet, who should have the starting obligation to present evidence in regard to this claim? Claims are statements about reality, and thus they are subject to truth. It seems obvious that Bob is the one who must present evidence for the truth of the claim as Bob brought the claim into being in the first place, and is thus responsible for it. To think otherwise means that Alice would be treated as a thief unless she could prove she was not a thief. In effect, Alice would have an obligation imposed on her merely from Bob decreeing an unsubstantiated claim about her. “Guilty until proven innocent” is an affront to justice, whether one identifies as a libertarian or not.

To pursue justice is to pursue the truth. To use unsubstantiated claims as a justification to use force is to weaponize the process of “justice” into something wicked.

We can’t know that immigrants will commit crimes once they enter the country just because other immigrants have a history of committing crimes any more than we can claim to know that parents who committed crimes when they were children will produce offspring that will commit crimes in the future. In philosophy, this type of problem is known as “The Problem of Induction”. Inductive reasoning is the act of observing certain particulars and inferring from those particulars a generalized conclusion, I.E. “Alice pulled 5 rotten apples out of a basket of 10 in a row and concluded that all the apples in the basket were all rotten”.

The problem arises because there is no way we can know with certainty through induction that the sum of the generalized set shares properties with the observed particulars, nor do we know that these properties won’t change in the future. Induction can be an expedient path, but it is a path often draped in epistemological darkness.

All of this taken together should show that the immigrant must have the presumption of innocence, in the same way, you or I would if we were accused of a crime if Justice is to prevail.

The libertarian must never fall prey to the allure of expediency that generalization provides when Justice demands otherwise.

𝑾𝒉𝒂𝒕 𝒕𝒐 𝒅𝒐 𝒊𝒏 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝒎𝒆𝒂𝒏𝒕𝒊𝒎𝒆?

Engrossed in the libertarian enigma of immigration is the question of who has the legitimate ownership of the “public spaces”. (I’ve offered my answer above, but I want to bring forth another argument I have yet to address before we close.)

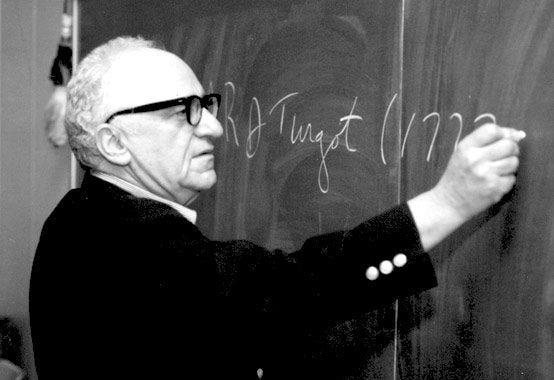

The father of modern libertarianism, Murray N. Rothbard wrote a challenging critique in chapter 40 of “Making Economic Sense” 4 titled: “WHAT TO DO UNTIL PRIVATIZATION COMES”

Rothbard asserts that until we reach a private property society, all public property should be treated as if it were private in order to establish certain norms on the property that are not possible if the property is open to everyone.

Rothbard writes:

But what should be done in the meantime?

There are two possible theories. One, which is now predominant in our courts and among left-liberalism, and has been adopted by some libertarians, is that so long as any activity is public, the squalor must be maximized. For some murky reason, a public operation must be run as a slum and not in any way like a business, minimizing service to consumers on behalf of the unsupported “right” of “equal access” of everyone to those facilities. Among liberals and socialists, laissez- faire capitalism is routinely denounced as the “law of the jungle.” But this ”equal-access” view deliberately brings the rule of the jungle into every area of government activity, thereby destroying the very purpose of the activity itself. For example: the government, owner of the public schools, does not have the regular right of any private school owner to kick out incorrigible students, to keep order in the class, or to teach what parents want to be taught.

The government, in contrast to any private street or neighborhood owner, has no right to prevent bums from living on and soiling the street and harassing and threatening innocent citizens; instead, the bums have the right to free “speech” and a much broader term, free “expression,” which they of course would not have in a truly private street, mall, or shopping center. Similarly, in a recent case in New Jersey, the court ruled that public libraries did not have the right to expel bums who were living in the library, were clearly not using the library for scholarly purposes, and were driving innocent citizens away by their stench and their lewd behavior.

And finally, the City University of New York, once a fine institution with high academic standards, has been reduced to a hollow shell by the policy of “open admissions,” by which, in effect, every moron living in New York City is entitled to a college education. That the ACLU and left-liberalism eagerly promote this policy is understandable: their objective is to make the entire society the sort of squalid jungle they have already insured in the public sector, as well as in any area of the private sector they can find to be touched with a public purpose. But why do some libertarians support these “rights” with equal fervor? There seem to be only two ways to explain the embrace of this ideology by libertarians. Either they embrace the jungle with the same fervor as left-liberals, which makes them simply another variant of leftist; or they believe in the old maxim of the worse the better, to try to deliberately make government activities as horrible as possible so as to shock people into rapid privatization. If the latter is the reason, I can only say that the strategy is both deeply immoral and not likely to achieve success.

It is deeply immoral for obvious reasons, and no arcane ethical theory is required to see it; the American public has been suffering from statism long enough, without libertarians heaping more logs onto the flames. And it is probably destined to fail, because such consequences are too vague and remote to count upon, and further because the public, as they catch on, will realize that the libertarians all along and in practice have been part of the problem and not part of the solution.

Hence, libertarians who might be sound in the remote reaches of high theory, are so devoid of common sense and out of touch with the concerns of real people (who, for example, walk the streets, use the public libraries, and send their kids to public schools) that they unfortunately wind up discrediting both themselves (which is no great loss) and libertarian theory itself. What then is the second, and far preferable, theory of how to run government operations, within the goals for cutting the budget and ultimate privatization?

Simply, to run it for the designed purpose (as a school, a thoroughfare, a library, etc.) as efficiently and in as businesslike a manner as possible. These operations will never do as well as when they are finally privatized; but in the meantime, that vast majority of us who live in the real world will have our lives made more tolerable and satisfying.

Murray Rothbard is without a doubt one of my most foundational ideological influences, and I owe a great deal of gratitude to his work. With that being said, we should never allow our heroes to be beyond reproach, to do so would be a disservice to them, for they would surely respect honest critique as opposed to affirmation born out of cowardice.

While I certainly agree with Rothbard that the state’s control of these resources generates negative externalities for many, I do not think Rothbard’s argument here holds the weight he wishes. The assertion that it should be run like it was under the control of a private owner doesn’t tell us anything. There is no platonic ideal of what a private owner should do on the grounds of their property, and even if there was, it certainly could not be deduced from the libertarian axiom that Rothbard vigorously supported throughout his life. What one private owner would want to do on their property may be completely contrary to what another may wish to do on their respective property. The libertarian merely asserts that one has an exclusive claim to their property, they do not assert that there is a correct way for them to use their property vis-à-vis libertarianism.

To illustrate this, a person who runs his property communally where anyone is free to use his property is as much of a private owner dictating terms on his property as the property owner who restricts all but a certain few on a number of conditions is, as long as he acquired the property legitimately.

A private church and a private brothel are both equally private property in the eyes of the libertarian.

I would agree with Rothbard that the state doesn’t own the property in question, but this does not entail that the state has the right to use the property as if it was their private business, not because everyone has a right to it, but rather because this would be a rights violation of the legitimate owner’s claim, which can’t be justified on libertarian grounds.

The argument that Rothbard proposes above may be persuasive if viewed from a consequentialist or utilitarian lens, but the very libertarian foundation that Rothbard spent his life developing was not based on consequentialist or utilitarian considerations. I can only view Rothbard’s turn here as somewhat disappointingly inconsistent with his previous work, which stands as an indispensable cornucopia in the libertarian canon. If you agree with Rothbard’s argument here, that is understandable, but I don’t think you can claim this is Rothbard deriving something from his theory, and instead, should be viewed as a standalone proposition.

𝐖𝐡𝐨 𝐚𝐜𝐭𝐮𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐲 𝐨𝐰𝐧𝐬 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭?

I made the case earlier in this post that the true owners of the state’s publicly controlled property are the laborers/material suppliers that were defrauded by the state’s purchase of those materials and solicitations of labor with the use of stolen money. I would like to expand this claim and consider other possibilities.

Let’s imagine a state-controlled park. While I still hold that the person, group, or firm that supplied the materials and labor owns the park, I do not think this property title is eternally retained outside of contextual events.

To come to own something is to incorporate a currently unincorporated rivalrous resource of the world into your ongoing projects toward an end. If a person neglects their property for an extended amount of time and shows no indication of future use of the property, then one can make a case that the resource has become unincorporated and therefore abandoned.

If a resource has been abandoned, by Libertarian-Lockean norms, the resource is now legitimately open for homestead as it was prior to the original incorporation.

I would argue that while the park was originally owned, the owners have not shown any sign of retaining their claim. Thus, for most cases of “Public Property” in the U.S., I would claim the actual owners are the consistent users of the property in general, as they have homesteaded the now abandoned property. This means a public school is owned by the faculty and parents (by proxy of their children), a public library is owned by the faculty and perhaps its consistent users, and of course the same for the public park, etc.

Ultimately, this means the libertarian must intellectually defend the right of the property owners of these spaces to determine how they are used, and not the taxpayers at large merely because they are taxpayers.

In my view, all of this taken together leaves only one conclusion in regards to the correct libertarian position of state immigration enforcement: All state border enforcement is unjustified on libertarian grounds and if libertarians wish to be consistent in their framework, they should all support the abolition of all state border enforcement.

I understand that I’m challenging many libertarian presuppositions, and I respect what that entails. I can only hope I made my case adequately, and if I am wrong and made a glaring misstep in my logic, then someone can correct me and the truth will prevail either way, and we can continue to champion the rights of the individual, which is our ultimate cause as anarchists.

𝐒𝐩𝐞𝐜𝐢𝐚𝐥 𝐓𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐤𝐬

This was my first article on libertarian theory after being a devout consumer of libertarian books, journals, podcasts, etc, for 10 years. I deeply appreciate all who stuck through and even the ones who didn’t. I hope to be doing more of these on different topics (not always on the topic of libertarian anarchism) and I genuinely welcome all criticisms of the claims I made in this post.

Thank you!

𝑹𝒆𝒇𝒆𝒓𝒆𝒏𝒄𝒆𝒔

Hoppe, 2014. A Realistic Libertarianism (pages 16-17)

https://cdn.mises.org/A%20Realistic%20Libertarianism.pdf

Hoppe, 1998. The Case for Free Trade and Restricted Immigration Journal of Libertarian Studies 13, Number 2 (pages 226-227) https://cdn.mises.org/13_2_8_0.pdf

Long, 1996. In Defense of Public Space https://www.panarchy.org/rodericklong/publicspace.html#ethical

Rothbard, 1995. Making Economic Sense - Chapter 40 What To Do Until Privatization Comes (Pages 146-150) https://cdn.mises.org/Making%20Economic%20Sense_3.pdf

Just tell people: "I firmly believe that net taxpayers want open borders and we should best approximate that." Any objection also applies to the opposite.

Great writing and detail -- as someone who's still got plenty of libertarian literature to learn, I found what you had to say very informative. I definitely agree that libertarians should never be tempted into the trap of utilitarian thinking even if it may seem the most palpable and familiar.

And I liked your analogies highlighting the danger of punishing someone for what they might do. I employ a similar argument against the covidian fanatics who support covid vaccine passports and justify it because it forcefully segregates x person (the unvaccinated) due to their propensity or possibility of spreading x germ (covid). It's an egregious fallacy that as I have often brought up, would justify the incarceration of black youth because of their statistical likelihood to commit crime.

What happens to the public property if the State were to just vanish is definitely a complex and difficult question to answer. There really is no "right" answer, albeit maybe the most theoretically consistent. I am similarly inclined to favor, naturally, those whom occupy or use it presently. For example, a government housing unit would go to the tenants actually living there. Albeit I see issues that could arise -- and it could get rather messy when it comes to schools and libraries where there is a lot of people involved in its upkeep and use.

For example, in a school there are teachers, students, parents, janitors, the bookkeepers and other executive positions that are involved in its maintenance, etc. . Implying the school or library became a sort of homesteading 'unclaimed' space, I suppose for any sort of profitable future the inhabitants of the school for example may collectively decide to auction it off or some other means as to further privatize it into a more efficient business.

The immigration-border issue is one I admit I am still pondering but it was insightful to see your excerpts and rationales. I am definitely in favor of whatever solution being as decentralized as possible and to throw any and all centralization out of the window. I look forward to reading more of your work and I hope my two cents has proved useful in some kind.

And with all that said, it's good to see more fellow liberty-minded writers carving out the liberty space on the Substack platform. I'm similarly doing some libertarian writing of my own, feel free to check my Substack out and subscribe if you wish <3